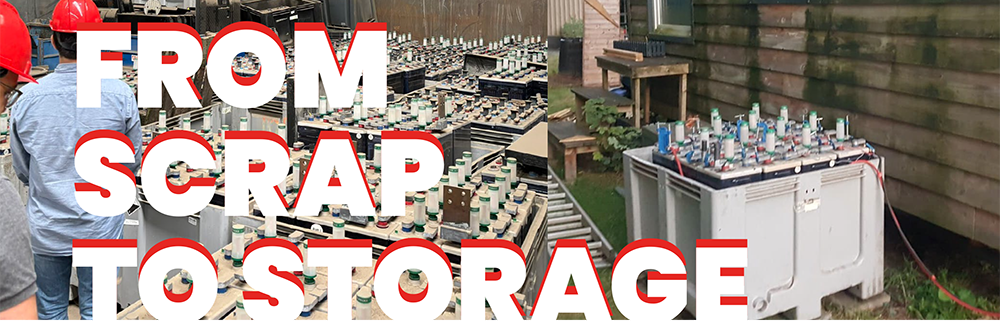

Imagine a warehouse full of tons of discarded lead-acid battery cells—rusted, sulphated, destined for recycling. What if, instead of melting them down, many of them could be refurbished and used again as energy storage? That’s the idea behind the ReLAB project, a collaboration between Riwald Recycling and the Fraunhofer Innovation Platform for Advanced Manufacturing at the University of Twente (FIP-AM@UT). Over the past half year, a framework was developed and tested to assess, and potentially recondition, salvaged flooded lead-acid batteries in real-world settings.

Turning Waste into Opportunity

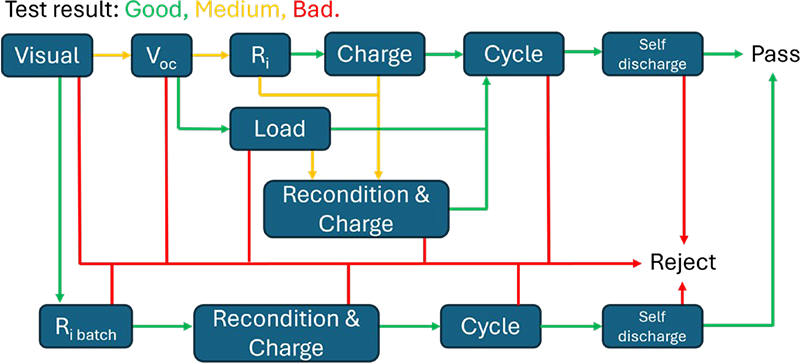

Lead-acid batteries are among the most recycled consumer products in the world, with industry-leading recovery rates in Europe and the U.S. But that doesn’t mean reuse is common. Typically, discarded batteries are crushed and smelted—with no attempt to see whether they still hold useful capacity. As many cells are replaced “too early” to prevent failures, there’s a real opportunity to extract extra value. My research thesis takes on that opportunity through the development of a decision-tree framework that combines fast screening tests (visual inspection, voltage, internal resistance, and self-discharge) with deeper cycle testing and reconditioning steps. The goal: filter out cells that are truly dead while rescuing those that can offer years of secondary service.

What We Found: 43 Tonnes, Hundreds of kWh

Applying the framework to Riwald’s stock, more than 500 cells were screened. As expected, many were in poor condition—cracked cases, heavy sulfation and failed visual checks. But the results were surprisingly significant: nearly half of the Hoppecke cell batch showed enough potential for reuse (either directly or after reconditioning). This finding represents several hundred kilowatt-hours of energy storage capacity otherwise headed for the smelter.

Importantly, the framework allowed clear categorization: cells marked for reuse, cells to recondition, and cells to recycle—helping Riwald optimize logistics and avoid unnecessary transport of unusable material.

Decision-tree framework for discarded lead-acid batteries

Real-World Trials: FIP’s shopfloor & Off-Grid Tiny House

Two case studies were conducted to pilot the framework in real-world conditions:

At FIP’s shopfloor (grid-connected), salvaged batteries were tied into a 12V storage system and a 24V UPS. The system managed stable charge/discharge cycles using commercial inverters; the UPS managed to bridge outages for 3D printers and this could be extended to other applications. While the battery size was small relative to FIP’s energy demand, the demonstrations proved technical viability and offered valuable lessons in control, safety and monitoring. The system can now be used as a demonstrator at FIP.

At a tiny off-grid house, the system operated under variable solar input. Performance was modest—round-trip efficiency around 42%—but the results demonstrated that even in a small-scale setting, salvaged batteries can provide resilient energy, especially when cost and robustness are primary goals. In both cases, key challenges emerged: cell imbalance skewed results, handling 100 kg cells needs special equipment and connections were imperfect. Nonetheless the experiments validated that second-life LAB systems can work outside the lab to provide real value.

Why It Matters: Profit, Planet & Practice

This work sits at the intersection of economics, sustainability and industrial practice, while maintaining societal (safety) considerations. For recycling firms like Riwald, it proposes a value add stream beyond metal recovery.

For renewable energy adopters, it offers a low-cost storage option that fits in stationary contexts where weight or size are less critical, such as for electrical cranes or construction site power solutions. And for the planet, it delays energy-intensive smelting and reduces raw material demand.

Of course, reuse isn’t without trade-offs. Efficiency is lower compared to lithium technologies, and the weakest cell in a pack can drag down performance. But in applications that prioritize robust, fire-safe and cheap storage, salvaged lead-acid systems can serve niche markets and bridge gaps in the circular economy.

What Comes Next?

The next steps from here include:

Scaling up: testing the framework at other recycling facilities, with different cell types and larger volumes.

Economic modelling & LCA: building precise cost and environmental impact models using real operational data.

Policy & industry uptake: working with certifiers, energy regulators and battery manufacturers to validate reuse pathways.

Battery Design: Riwald is interested in using all salvageable cells in a big grid connected storage system, contributing to overall grid stability.